The Village Voice

"Roxy Paine Will Warp Your Brain"

by Christian Viveros-Faune

'What produces a present as different, and how does a present focus a past in turn?" A simple question asked in convoluted academic patois, the query kicks off Hal Foster's introduction to The Return of the Real, at one time a massively influential treatise on contemporary art. Published in 1996, the book articulated art's postmodern (and some say rightward) turn toward anti-enlightenment critique. Rather than continue the "metaphorical" tradition that ran from Picasso through Pollock, Foster strategically fomented the kind of (purportedly) "realist" analysis — deconstruction, demystification, discourse debunking, etc. — that specialist critics like him applied to (supposedly) cerebral artists like Duchamp and Warhol. The idea was to promote the triumph of theory over metaphor. If shows like "Denuded Lens," Roxy Paine's trompe l'oeil exhibition of meticulously carved wood sculptures at Chelsea's Marianne Boesky Gallery, are any indication, that idea has finally tanked harder than Jeff Bezos's 99-cent Amazon phone.

A problem-rich exhibition of the claptrap-free variety, Paine's current collection of hand- and machine-tooled objects needs zero critical theory to be understood but plenty of close-up looking to plumb its eye-fooling secrets. The exhibition's title suggests a connection to photography but also to seeing things without certain meddlesome habits of mind, including jaded skepticism, received opinion, and blinkered ideology. In his new show, Paine basically establishes his own investigatory bona fides — like, say, J.J. Gittes in Chinatown. That's great news for viewers and critics alike; his art has long been about confecting enduring visual mysteries. In this artist's hands, seemingly familiar objects routinely turn compelling, strange, and noir. (Full disclosure: I wrote an essay for a pamphlet that accompanied another exhibition of Paine's work in Chicago last year.)

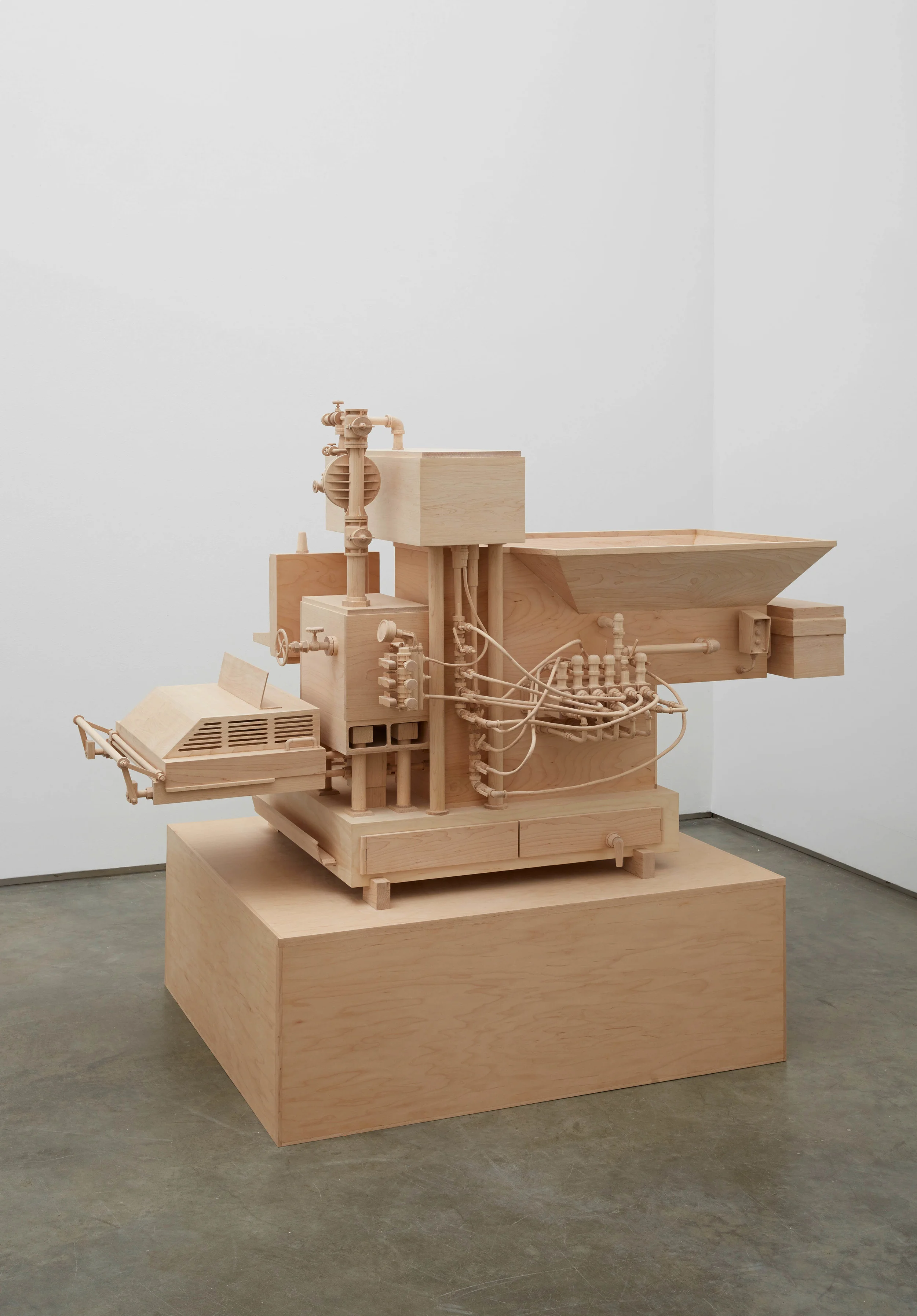

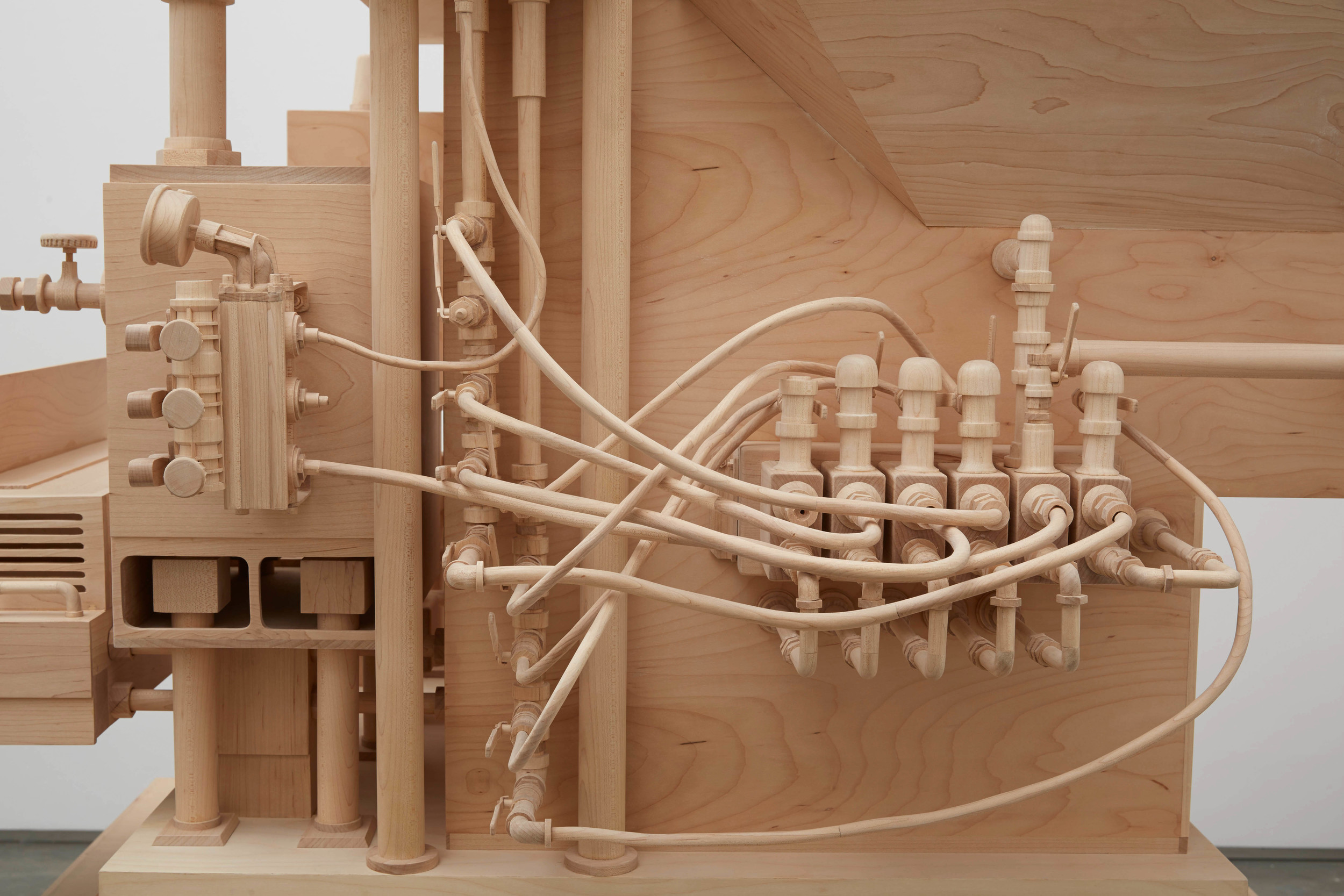

Take the lathed wooden "machines" Paine locates near the entrance to the gallery like bouncers at the entrance to the Stork Club. Full-scale objects made entirely from unfinished maple, they mimic certain industrial components while at the same time ghosting the utility they so convincingly fake. The first such work, Scrutiny, consists of a solid tabletop overwhelmed by a load of counterfeit devices: a clip-on light, several cameras, a microphone, a calculator, and a telescope, all made of wood. The second, Machine of Indeterminacy, presents an assembly-line component whose levers, plugs, chutes, and conduits, all expertly carved from maple, fail to add up to any discernible functionality. A question lingers: If not pitch-perfect copies of things in the world, what are Paine's surrogates about? In an interview with theBrooklyn Rail, the artist reluctantly describes his sculptures as reminders of the way "a human can be subject to scrutiny from every possible angle." More to the point, Paine's beige objects constitute knotty but capacious metaphors for the idea of "control."

Sculptures that feature a great big question mark at their core, these and two other artworks installed in the gallery's third space present a kind of foreword and afterword to the exhibition's main attraction (about which more later). Titled Intrusion and Speech Impediment — the former features a chiseled pinball machine crossed with a jagged topography, while the latter marries a carved chainsaw with a facsimile of a bullhorn — these two fantastical objects operate according to the same enigmatic logic that animates the exhibition's other stand-alone sculptures. Juxtapositions of one or more unrelated elements rendered with rare precision, they function principally by stretching the limits of what Samuel Taylor Coleridge cannily called the willing suspension of disbelief. This is Paine assuming the role of the artist as a storyteller. A sculptor in radical Borges mode, he also clearly relishes the idea of letting the viewer freely complete his strange sculptural fictions.

If Paine's sculptures consistently interrogate their forms and materials, the exhibition's centerpiece proves an inquisition: It takes the elements the artist harnesses in discrete pieces and puts them through the wringer. A Natural History Museum-type diorama of an airport security area — complete with full-body scanners, X-ray conveyor belts, plastic trays, and trash cans for liquid containers larger than 100 milliliters — Checkpoint moves beyond the precision of wayward replicas into a meticulously wood-carved parallel universe of anamorphic and cognitive distortion. Not only are materials like metal, plastic, and glass transformed into wood, but, thanks to the alchemy of forced perspective, some 80 linear feet of space are scrunched into 18 feet. The effect is a mind-blowing trip to Pleasantville. Employing computer modeling and uncanny realism, Paine has rendered an anxiety-inducing, product-of- our-times environment into something appropriately warped and colorless. Could there be a more apt scenario in which to take issues concerning perception and how we frame information and knowledge and subject them to the third degree?

A truly useful question about art's place in the world today might ask: How can visual art advance crucial cultural, social, and philosophical ideas? Roxy Paine's answer involves independent thinking, sleight-of-hand construction, and works that are rich in metaphorical depth. That's critical realism, all right — but for real this time.

September 2014