zingmagazine

Roxy Paine: Dunk/Redunk; Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York, New York

by Janet Goleas

Brooklyn, NY

1997

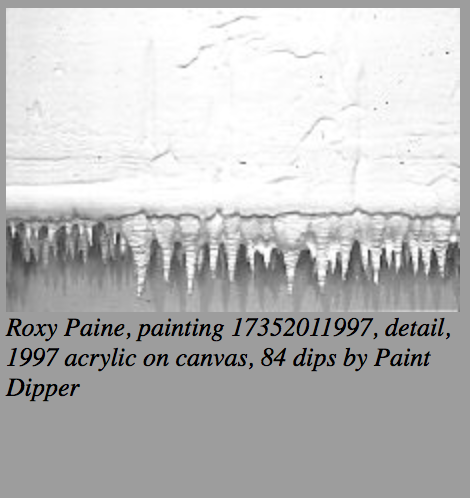

paint dipper is an imposing mechanical device which routinely and unceremoniously submerges fresh stretched canvases into a narrow steel tank of thick white paint. Operated by an absurdly small Macintosh Powerbook protected from paint splatters by a tiny sheet of Plexiglas, the electronic dipping vehicle automatically dunks and then redunks each canvas at two and a half hour intervals. Until completion the canvas hovers over the contraption, dripping and drying, as if catching its breath before the next plunge. The fruit of this repeated dunking is a bulging, tumorous rectangle, it's geography caked with dappled paint and thickly dribbled stalactites. Beautiful, really. And ripe with associations to the culturally over-saturated canvas, be it minimal or maximal.

So what is paint dipper? A refined torture device? Why am I thinking of the Salem witch trials? And what exactly does Roxy Paine have against painting? Well, nothing, I suspect. And that's one of the very salient things about his most recent show at Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. Although Paine appears to be ferreting out the utilitarian properties of a culture which has long since ceased to find a primary use for them, he is doing so with rancor or polemics. He's funny. It's not as though he has an ax to grind. He is, I think, interested in reducing certain cultural forms to their quantifiable elements, but happily, it is not an act of systematic sleuthing, finger-wagging, or disdain. On the contrary, he is inquisitive, almost guileless in his recapitulation of the facts, as if he is a brilliant feral child who has been presented with the task of distilling a cultural milieu with which he has never had direct contact. Of course, this is not exactly the case. Paine is of this world, but it seems he is methodically investigating the tools of modern culture, dismantling them word for word and then reassembling them in a way in which has, at least for him, been emptied out of its original power to transform.

Paine has removed the artist's hand from the process of painting in paint dipper, and replaced it with evidence of a simple mechanical history. The layered white paint, much like coats of primer, functions as if the painter is performing an endless act of preparation, priming and repriming the surface. As if the untouched canvas is already so full of imagery, expression and information that there is little point--or perhaps little pleasure--in covering it with anything else. Nowhere is Paine's tongue more firmly planted in his cheek than in this sculpture.

In model for painting, Paine disconnects an array of brush strokes from their probable destination--presumably the canvas--and catalogues the random facsimiles of paint in a glass-covered wall vitrine. Isolated from their original intent, the assemblage looks much like a Smithsonian display of highly informative ancient crockery which is missing too many parts to reassemble into a whole. In theory, this piece, like floor model, can be reconvened to create the likeness of a work of art, a little bit like assembling a model airplane. But at the Smithsonian, the fractured antiquities, no longer functional as utilitarian objects, take on an entirely new meaning as a visual model of ancient cultural habits. Separated from their usefulness, their functionality is redefined to fulfill a modern analysis of ancient technique and virtuosity, so that other cultural galaxies can look upon them for reassessment of historical accounts.

Similarly, here Paine is commenting on the formal tools of painting and sculpture, reminding us, perhaps, how they have been ravaged by overuse and consumerism and what precious little authenticity remains. Or perhaps that these basic utilities have been so codified and categorized that anyone can find equal or better goods in a blister pack at the bottom of a box of Cheerios. But primarily, I think he just wants to poke fun at an artistic milieu which has lost its tooth.

And then there is the nefarious mushroom, the divinely perilous fungus which can alternately amuse, inspire, poison or heal. mushroom field (psilocybe cubensis) is a delicate bed of perfectly hewn mushrooms. Replicas, that is, of hallucinogenic mushrooms--or mushroom sculptures--expanding across a good part of the gallery floor. And much like their renowned capacity to transform, indeed they cultivate a transformation right on Mercer Street by creating the illusion of a damp, earthen paradise sprouting before our eyes.

Hallucinogens, associated throughout the ages with creativity and the throwing off of psychological coils, are a means to an end much like brushstrokes and sculptural components, much like cultural tenets. And they may offer, in their most refined state, an alternative vision of reality.

But this is not a field of mushrooms, it is a facsimile of a field of mushrooms. Divorced from their natural environment and stripped of their magical properties, they are nostalgic, touching, whimsical. Intertwined with metaphors of myth, science, psychology and aesthetics, here Paine's use of artifice addresses issues of forgery and replication. And the artist's hand, responsible for, and yet eclipsed by, the astounding realism of the mushrooms, is also at issue, where evidence of the human touch is implicit but invisible. In poison ivy field (toxicodendron radicans), a diorama of plastic poison ivy proliferates in a weedy underbrush. One's reflexive "don't touch" resounds, as memories of bare-legged walks in the woods are conjured up. But is it frightening or is it satire? If it's a counterfeit patch of ivy, is it a counterfeit reaction? If ambivalence pervades the work, it is as a fined tuned metaphor in and of itself. While Paine's works are idea-driven, part of the machinery that drives them is the irony of his loose ends.